Thousands of people were in Istanbul's Cağlayan neighbourhood today to protest Pope Benedict XVI, who is due in Turkey in Tuesday. There was widespread booing, quite a lot of flag-waving, and many women turned up wearing headscarves and bandanas, clutching bemused babies. It was all organised by the Felicity Party (SP), the successor to the Welfare and Virtue parties that were closed down over the last ten years.

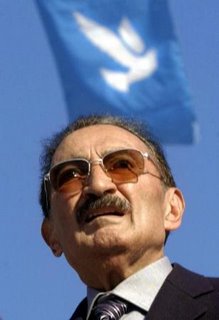

Thousands of people were in Istanbul's Cağlayan neighbourhood today to protest Pope Benedict XVI, who is due in Turkey in Tuesday. There was widespread booing, quite a lot of flag-waving, and many women turned up wearing headscarves and bandanas, clutching bemused babies. It was all organised by the Felicity Party (SP), the successor to the Welfare and Virtue parties that were closed down over the last ten years.In his frail state, former party leader and prime minister Necmettin Erbakan made an appearance via videolink to say he had no doubt the Pope was coming to resurrect Byzantium in Turkey. Other party officials egged on chants along the lines of "Don't turn the Hagia Sophia back into a church", as current SP leader Recai Kutan spoke out against the European Union.

Security was high at the demonstration, as anyone not carrying SP credentials had their banners confiscated. It did not go unnoticed either that separate protest areas had been allocated for men and women. It was a rather large gathering, with participants from all over the country. It caught the international headlines too - the BBC went with "Turkish protests at Pope's visit" while CNN said 20,000 people attended.

All in all though, it was a rather minor protest from what has become a fringe party. Benedict XVI's visit - a first papal visit to Turkey in many a year - is set to go ahead from Tuesday, and the good news is that he might just meet the sitting prime minister after all. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had earlier made his excuses for not meeting the Pope, pointing to the schedule clash with a NATO summit in Latvia.

It was slated by domestic commentators as a convenient excuse from a man with a history in political Islam. In its leading article tomorrow, The Times calls it a "snub". But in an eleventh hour rescue, Foreign Minister Abdullah Gül announced the Pope's timetable had shifted forward, and the two are likely to meet at Ankara airport after all. It sends out a positive signal - far from avoiding the Pope, Mr Erdoğan's government has worked to make a meeting, albeit a short one, possible.

"As a government we see the visit as an opportunity," said Mr Gül. "There are many misconceptions about Turkey, but Turkey is a country where tolerance occurs. We hope the visit helps dispel some of the misunderstandings between Muslims and Christians."

The tension that so clearly exists over the upcoming visit has not been helped by Pope Benedict himself, and the lack of forethought over his words for which he becoming notorious. Aside from his controversial Bavarian lecture in September, Benedict XVI managed recently to reiterate his views against Turkey's EU membership, and several Turkish newspapers have him saying at this Sunday's mass that his visit to Istanbul is "another crusade". Ho-hum.

There's a lot hanging on this next week, and the The Times's leading article is absolutely right: to achieve (it all) against a background of rising Muslim suspicion will demand all Benedict's tact, adroitness and humility.